Written by John S. Wilkins

A little while back I linked to Sahotra Sarkar’s review of Steve Fuller’s Science versus Religion. Now Fuller has put up a defence at the Intelligent Design website, Uncommon Descent, under the gerrymandered image of a bacterial flagellum (if you want to know what a real flagellum would look like at that scale, see this).

While I haven’t yet read the book (I’ll be reviewing it for Metascience), a couple of points that Fuller’s post make clear:

1. He has a really casual dismissal of factual accuracy so long as the “spirit” is right

2. This explains why he’s allied himself with ID.

Intelligent design is (as the link above showed) very cavalier with details and facts. The “impression” of design is reason enough to ride roughsod over the details. In fact, as the flagellum indicates, mostly their argument is argument ab cartoon – if you squint hard, then it looks like a machine. Imagine a physicist doing that and coming up with a cartoon physics!

Fuller derides Sarkar for caring about factual claims in detail, when the point is that… what? That you can make history say anything you like if you ignore historical data? Here is his defence of a few claims:

Let me take the following two criticisms together:

“Logical positivists, and not just Popper, are supposed to have labeled Darwinism a “metaphysical research program” (p. 133). I am not aware of a single logical positivist (or logical empiricist) text that supports this claim. Given that for the logical positivists (in contrast to Popper) “metaphysical” was a term of opprobrium, it is unlikely that any of them would have embraced this formulation. The logical positivists may well have believed physics to be of more fundamental importance than biology, but the latter science nevertheless belonged to the pantheon. The foundations of biology were intended to be part of their Encyclopedia of Unified Science.”

“Around the same time, Lamarck is supposed to have held that “lower organisms literally strove to become higher organisms, specifically humans, who at some point in the future would be Earth’s sole denizens” (p. 146), a view to be found nowhere in the Lamarckian corpus.”

These criticisms illustrate what I have called the ‘New Yorker magazine view of the world’ that afflicts some analytic philosophers. (I originally made this claim against a philosopher who actually began his career as an editor. Oops!) It basically reduces the history and philosophy of science to checking for facts and grammar, respectively. However, as so often is the case when dealing with editors, the fact-checker goes astray when he decides to venture opinions of his own. So even if it is strictly true that only Popper called Darwinism a ‘metaphysical research programme’ and the official logical positivist line was anti-metaphysical, it is equally true that the positivists themselves did metaphysics in everything but name (e.g. Carnap’s Aufbau), not least in the IEUS volume on biology that attempted to lay down the discipline’s axiomatic foundations. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that Popper wrote the obituary for its author, Joseph Woodger, in the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science in 1981.

On the point concerning the ‘Lamarckian corpus’, again I am happy to concede that the man himself never explicitly stated the thesis I attributed to him. As it turns out, the passage Sarkar quotes refers to Lamarck and Comte together as representatives of a pro-human line of evolutionary progress that was opposed to the more ecocentric line taken by Darwinists attempting to influence British sociology in its early years. Whatever Lamarck’s actual views on the ultimate fate of humanity (which are up for debate), it is clear that the Lamarckian tradition has been generally committed to what the historian Charles Gillispie called an ‘escalator of being’ on which all creatures were moving, with humans currently on the top floor. A clear expression of the view I attributed to Lamarck can be found in his most visionary 20th century follower, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who envisaged the Earth as someday becoming one ‘hominised substance’.

Now anyone who has studied logical positivism and Popper knows well that Popper resiled from the LPs’ claims to be metaphysics free. They held that metaphysics was something one ought not to do, in favour of positive knowledge. They held the famous Verification Principle, which Popper among others used as a reductio of the LP program. To say that they “were” doing metaphysics is to fundamentally mischaracterise what was going on. They claimed not to be. It was the critics, including Popper, who said they were. And so when Popper called Darwinian evolution a metaphysical research program, he clearly did not intend that as a criticism, even before his retraction. The positivists thought that was a criticism, but they didn’t make it. Post hoc assertions that they were one and the same is to completely mischaracterise what was going on then.

Fuller is well read. He should and probably does know this, so only two other interpretations are possible: carelessness, which undercuts the veracity of the argument, or mendacity, which also does. I like to think that Fuller is being careless rather than trying to deliberately mislead. But if that is his approach to the history of ideas, then I think there is a problem, Houston. Of course Popper wrote Woodger’s obit – that’s what victors do if they can. It doesn’t mean they get amalgamated with their former opponents. To say otherwise is to completely misunderstand the nature of dialectic.

Likewise the point about Lamarck. Lamarck, in what I have read (hey, the Zoological Philosophy is online in French and English; check for yourself) held that there was an impetus driving evolution “upwards” (a physical impetus, by the way – since Vance Alpheus Packard’s 1901 work, we have known that Lamarck did not mean “will” by “besoin”) but that individual lineages could not enter a filled “rung” on that ladder. And so far as I know, he never said anythign even remotely like that view that only humans would remain. Appealing to what others might have thought after Lamarck is in no way a justification of that very bad claim. And even Teilhard did not think there would be nothing but the Omega Point, merely that humanity would become one at that point in a kind of cosmic salvation.

This disregard for facts, so far from being a corrective to the “New Yorker” approach, is merely a Marvel Comics form of philosophy and history, and it’s the only kind that can support ID. I think the less of Fuller just for this one claim. I can only imagine what the full work will lead me to think of him.

Packard, Alpheus. 1901. Lamarck, the founder of evolution: His life and work. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Quick: how many phases of water are there? If you answer three (liquid, gas, and solid) you’d be wrong. There are at least 5 different phases of liquid water and 14 different phases (that scientists have found so far) of ice.

Quick: how many phases of water are there? If you answer three (liquid, gas, and solid) you’d be wrong. There are at least 5 different phases of liquid water and 14 different phases (that scientists have found so far) of ice. In the alternative medicine of homeopathy, a dilute solution of a compound can have healing effects, even if the dilution factor is so large that statistically there isn’t a single molecule of anything in it except for water. Homeopathy proponents explain this paradox with a concept called “water memory” where water molecules “remember” what particles were once dissolved in it.

In the alternative medicine of homeopathy, a dilute solution of a compound can have healing effects, even if the dilution factor is so large that statistically there isn’t a single molecule of anything in it except for water. Homeopathy proponents explain this paradox with a concept called “water memory” where water molecules “remember” what particles were once dissolved in it.

If your inbox is anything like ours, you get a regular stream of YouTube links from friends, relatives, friends-of-friends, friends-of-relatives-of-friends … and you only occasionally click through. Gmail add-on

If your inbox is anything like ours, you get a regular stream of YouTube links from friends, relatives, friends-of-friends, friends-of-relatives-of-friends … and you only occasionally click through. Gmail add-on  You’ll have to excuse the horn-tooting, but we’ve put together a Firefox extension that combines some of the best JavaScript we’ve seen for YouTube and makes them all in check-on, check-off usable for any Firefox browser. The

You’ll have to excuse the horn-tooting, but we’ve put together a Firefox extension that combines some of the best JavaScript we’ve seen for YouTube and makes them all in check-on, check-off usable for any Firefox browser. The  There are a lot of great live performances lurking around YouTube, many of which have never seen the light of day in the recorded audio realm. To jump those jams into your playlist, use a web-based converter like

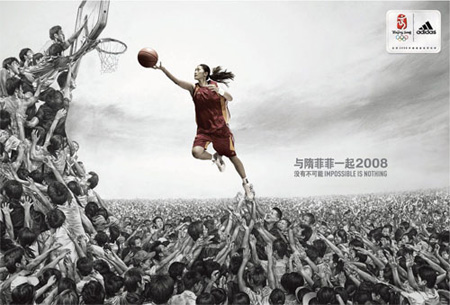

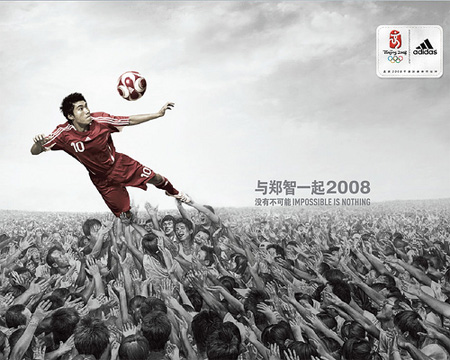

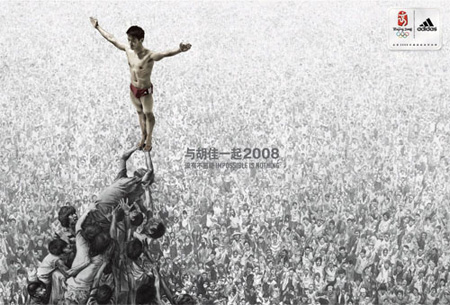

There are a lot of great live performances lurking around YouTube, many of which have never seen the light of day in the recorded audio realm. To jump those jams into your playlist, use a web-based converter like  This summer’s Olympics has been a good lesson in the necessity of working around networks’ and video providers’ often ridiculous restrictions based on location and timing. On YouTube, there’s often a simple work-around, as

This summer’s Olympics has been a good lesson in the necessity of working around networks’ and video providers’ often ridiculous restrictions based on location and timing. On YouTube, there’s often a simple work-around, as  Free video timeline creator

Free video timeline creator  You could, if you wanted, keep track of all your favorite net-based video shows in a feed reader or just wait to hear about them a week after they’re released. Or you could use the free, cross-platform

You could, if you wanted, keep track of all your favorite net-based video shows in a feed reader or just wait to hear about them a week after they’re released. Or you could use the free, cross-platform  YouTube offers up a few RSS feeds of videos-“Recently Featured,” “Top Favorites Today,” and the like-but not for inpidual searches, the kind you’d make if you were keeping up with The Guild or keeping on top of the latest Xbox 360 hacks.

YouTube offers up a few RSS feeds of videos-“Recently Featured,” “Top Favorites Today,” and the like-but not for inpidual searches, the kind you’d make if you were keeping up with The Guild or keeping on top of the latest Xbox 360 hacks.  Many web videos are perfect for quick desktop scanning, but YouTube also contains entire series and longer clips-especially those with higher resolutions available-that make for great couch fare. If you’ve got a classic Xbox or a Windows Media Center hooked up to the tube, you can flip your Xbox into a

Many web videos are perfect for quick desktop scanning, but YouTube also contains entire series and longer clips-especially those with higher resolutions available-that make for great couch fare. If you’ve got a classic Xbox or a Windows Media Center hooked up to the tube, you can flip your Xbox into a  If you want to stash a YouTube clip away for editing or watching without the net, you’ve definitely got options. Internet Explorer users might appreciate

If you want to stash a YouTube clip away for editing or watching without the net, you’ve definitely got options. Internet Explorer users might appreciate

Just a temporal hop, skip and a jump away is 2009’s live-action big screen version of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, but if the American adaptation of the manga/anime phenomenon that launched a thousand otaku is a smash success, what treasured classics of Japanese culture will Hollywood choose to to adapt next? Below the jump, we put on our robe and cultural raider hat and pick five golden temples of science-fiction manga and anime for studios to pillage and plunder.

Just a temporal hop, skip and a jump away is 2009’s live-action big screen version of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, but if the American adaptation of the manga/anime phenomenon that launched a thousand otaku is a smash success, what treasured classics of Japanese culture will Hollywood choose to to adapt next? Below the jump, we put on our robe and cultural raider hat and pick five golden temples of science-fiction manga and anime for studios to pillage and plunder. Super Dimension Fortress Macross: Well, yeah. Big ass robots are pretty much a given, what with the success of Transformers. And while the mecha of SDMF don’t transform into cool cars or panty vending machines, they have a secret weapon in the battle for big money franchises: this epic tale of war between humanity and an alien race was adapted as the first segment of the Robotech cartoon. That series, which ran in the U.S. in 1985, gave many Americans their first crucial taste of anime action filtered through a sweeping storyline. As if that wasn’t enough, Super Dimension Fortress Macross features a love triangle between two military officers and a pop idol, enough twists and turns to put Battlestar Galactica to shame, and characters with big, big hair. Like, “hey, I could skydive onto that,” big. Once he’s through having his way with Watchmen, we want to see Zack Snyder take Super Dimension Fortress Macross and make it the big screen franchise of cheesy awesomeness most of us have been waiting for without even knowing it.

Super Dimension Fortress Macross: Well, yeah. Big ass robots are pretty much a given, what with the success of Transformers. And while the mecha of SDMF don’t transform into cool cars or panty vending machines, they have a secret weapon in the battle for big money franchises: this epic tale of war between humanity and an alien race was adapted as the first segment of the Robotech cartoon. That series, which ran in the U.S. in 1985, gave many Americans their first crucial taste of anime action filtered through a sweeping storyline. As if that wasn’t enough, Super Dimension Fortress Macross features a love triangle between two military officers and a pop idol, enough twists and turns to put Battlestar Galactica to shame, and characters with big, big hair. Like, “hey, I could skydive onto that,” big. Once he’s through having his way with Watchmen, we want to see Zack Snyder take Super Dimension Fortress Macross and make it the big screen franchise of cheesy awesomeness most of us have been waiting for without even knowing it. Parasyte: Hitoshi Iwaaki’s manga is the strangely satisfying marriage of Spider-Man and Invasion of the Body Snatchers: a failed attempt by an alien invader to take over the brain of Shinichi Izumi has left it in control of his right hand, and teen and alien must form an uneasy alliance to avoid being found out by Shinichi’s culture or killed by the aliens that have infiltrated it. Blending paranoia, frenzied fight scenes, and meditations on what it means to be human, Parasyte takes the most painful subtext of puberty-that your body has become something strange and not quite in your control, and now you’re an outsider as a result-and serves it up as delicious, delicious crazy. (No wonder Del Rey’s current adaptation is the second time the series has been brought to the USA.) Rumors abound that Jim Henson’s studio and producer Don Murphy are already working to bring it to the big screen, but screw that noise: let Peter Jackson get his hands on the material, and make it as a bloody bookend to his adaptation of Alice Sebold’s The Lonely Bones (and a loose companion piece to his classic Braindead (or Dead-Alive, as it’s known over here)).

Parasyte: Hitoshi Iwaaki’s manga is the strangely satisfying marriage of Spider-Man and Invasion of the Body Snatchers: a failed attempt by an alien invader to take over the brain of Shinichi Izumi has left it in control of his right hand, and teen and alien must form an uneasy alliance to avoid being found out by Shinichi’s culture or killed by the aliens that have infiltrated it. Blending paranoia, frenzied fight scenes, and meditations on what it means to be human, Parasyte takes the most painful subtext of puberty-that your body has become something strange and not quite in your control, and now you’re an outsider as a result-and serves it up as delicious, delicious crazy. (No wonder Del Rey’s current adaptation is the second time the series has been brought to the USA.) Rumors abound that Jim Henson’s studio and producer Don Murphy are already working to bring it to the big screen, but screw that noise: let Peter Jackson get his hands on the material, and make it as a bloody bookend to his adaptation of Alice Sebold’s The Lonely Bones (and a loose companion piece to his classic Braindead (or Dead-Alive, as it’s known over here)). FLCL: An Original Video Animation (OVA) from 2000, FLCL has a lot in common with Akira: you’ve got people hollering and jumping off motorized two wheelers while strange growths shoot out of the foreheads of pained adolescents. But whereas Akira takes creator Katsuhiro Otomo’s memories of growing up during the turbulent period of 1960s Japan and transmutes it into a serious sci-fi epic, FLCL stems from the shock contemporary culture can bring to a lonely kid growing up in a small town, whipping the story into a wild-eyed froth of rampaging robots, crazy vespa-riding women, and bass guitar centered fight scenes. Benjamin Button, Shmenjamin Shmutton: we want to see David Fincher in full-on Fight Club mode try to match the brio of this series’ animated anarchy.

FLCL: An Original Video Animation (OVA) from 2000, FLCL has a lot in common with Akira: you’ve got people hollering and jumping off motorized two wheelers while strange growths shoot out of the foreheads of pained adolescents. But whereas Akira takes creator Katsuhiro Otomo’s memories of growing up during the turbulent period of 1960s Japan and transmutes it into a serious sci-fi epic, FLCL stems from the shock contemporary culture can bring to a lonely kid growing up in a small town, whipping the story into a wild-eyed froth of rampaging robots, crazy vespa-riding women, and bass guitar centered fight scenes. Benjamin Button, Shmenjamin Shmutton: we want to see David Fincher in full-on Fight Club mode try to match the brio of this series’ animated anarchy. 20th Century Boys: The toast of scanlators worldwide and a huge hit in its native Japan, 20th Century Boys is the most ambitious work Naoki Urasawa has undertaken, spanning more than forty years, dozens of characters, and twenty-two collected volumes. (His previous work, Monster, was no slouch either-a crime thriller set in Eastern Germany that reads like a cross between The Fugitive and Silence of the Lambs, Monster ran for six years and was collected in eighteen volumes.) While 20th Century Boys takes its name from a T. Rex song, its hook seems like a Stephen King novel on steroids: a group of old friends in the ’90s try to figure out the link between a destructive cult leader and their forgotten childhood fantasies. Meanwhen, in 2014, a young woman tries to figure out what happened to them. While Lar von Trier has the chops to keep so many characters and so many stories moving along, he lacks the warmth and affection Urasawa brings to his characters. Let Best of Youth‘s Marco Tullio Giordana give it a shot-his five hour epic from 2003 covers a similarly vast swath of time.

20th Century Boys: The toast of scanlators worldwide and a huge hit in its native Japan, 20th Century Boys is the most ambitious work Naoki Urasawa has undertaken, spanning more than forty years, dozens of characters, and twenty-two collected volumes. (His previous work, Monster, was no slouch either-a crime thriller set in Eastern Germany that reads like a cross between The Fugitive and Silence of the Lambs, Monster ran for six years and was collected in eighteen volumes.) While 20th Century Boys takes its name from a T. Rex song, its hook seems like a Stephen King novel on steroids: a group of old friends in the ’90s try to figure out the link between a destructive cult leader and their forgotten childhood fantasies. Meanwhen, in 2014, a young woman tries to figure out what happened to them. While Lar von Trier has the chops to keep so many characters and so many stories moving along, he lacks the warmth and affection Urasawa brings to his characters. Let Best of Youth‘s Marco Tullio Giordana give it a shot-his five hour epic from 2003 covers a similarly vast swath of time. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Finally, if Hollywood is crazy enough to tackle such a groundbreaking classic as Akira, why not let it try other works of manga that’ve had an indisputable impact on the medium? Hayao Miyazaki may rule the world of Japanese animation now, but his anime adaptation of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, his own manga, was only able to cover approximately the first quarter of his tale. As long as Hollywood wants to bite off more than it can chew (for the profit to be garnered by pre-chewing material for the masses), why not have it mount a Lord of the Rings style cycle, covering the entire tale of a princess’s adventures a thousand years after our modern-day civilization has destroyed itself. Epic battles, environmentalism, more opportunities for CGI than you can shake a fistful of sticks at-they’ll eat up Nausicaä in the cineplexes, particularly if you get Alfonso Cuarón on board. Having directed such diverse work as Chldren of Men, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, and Y Tu Mama Tambien, Cuarón’s got the right amount of razzle-dazzle, hippie-dude humanism, and child-eyed wonder. To the extent such a thing can (or should be) attempted, Cuarón is the one to do it.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: Finally, if Hollywood is crazy enough to tackle such a groundbreaking classic as Akira, why not let it try other works of manga that’ve had an indisputable impact on the medium? Hayao Miyazaki may rule the world of Japanese animation now, but his anime adaptation of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, his own manga, was only able to cover approximately the first quarter of his tale. As long as Hollywood wants to bite off more than it can chew (for the profit to be garnered by pre-chewing material for the masses), why not have it mount a Lord of the Rings style cycle, covering the entire tale of a princess’s adventures a thousand years after our modern-day civilization has destroyed itself. Epic battles, environmentalism, more opportunities for CGI than you can shake a fistful of sticks at-they’ll eat up Nausicaä in the cineplexes, particularly if you get Alfonso Cuarón on board. Having directed such diverse work as Chldren of Men, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, and Y Tu Mama Tambien, Cuarón’s got the right amount of razzle-dazzle, hippie-dude humanism, and child-eyed wonder. To the extent such a thing can (or should be) attempted, Cuarón is the one to do it.